The special education student population in California and nationwide has grown in recent years. The reasons are complex and at least partially related to increased awareness and identification of various conditions, including learning disabilities, autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and emotional/behavioral conditions. As a result, more students who may have gone undiagnosed in the past are now being recognized and provided with the care and support they need.

Compounding this increase is the fact that there is currently an epidemic of mental health issues among young people, what, in 2021, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy called a “mental health crisis.” The pandemic compounded the already fraught landscape of adolescence, adding to a range of existing stresses and anxieties, including academic and social pressure, isolation due to excessive screen time, social media pressures, bullying, and economic pressures.

Together, students with disabilities and those experiencing mental health and behavioral conditions represent a group of the most vulnerable students in our schools, those most at risk for failing to connect educationally and socially. Educators and school districts are struggling to accommodate all of these nuanced and, at times, overlapping conditions. Significant State budget investments have attempted to address these issues, including Governor Newsom’s 2022 $4.7 Billion Master Plan for Kids Mental Health and other resources delivered through MediCal, strategies to bolster community schools, and efforts to expand the healthcare workforce.

Inclusion and Evolving Special Education Standards

While it is important to understand the more significant macro situation, special education and instruction for vulnerable students are day-to-day challenges addressed at an individual and campus level. To understand the planning and design challenges, you have to know a bit about the evolving history of special education. Before the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) passed in 1975, many students with disabilities were denied access to education and opportunities to learn.

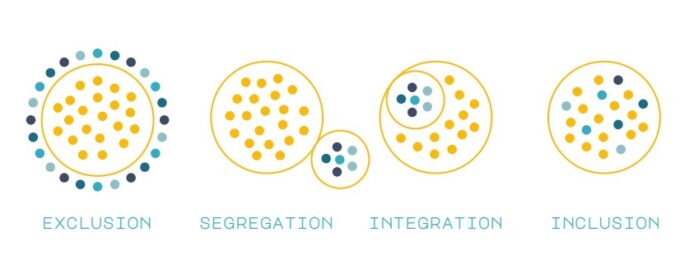

There was an “institutional” thinking and approach which carried with it stigma and worse. Since the passage of the EHA, the distinct field of Special Education emerged, including a legal framework that guaranteed access and accommodation for all students. With the law’s name change to Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), students with disabilities are receiving special education and related services today designed to meet their individual needs alongside their peers to the maximum extent appropriate and possible—a practice known as “Inclusion.” Extensive research over decades has shown that an inclusive approach creates a more diverse and accepting learning environment, minimizes stigma, and delivers significant social and academic benefits for special education students and their general population peers. Inclusion allows for more complete educational opportunities that have been shown to translate into greater chances of success after high school for students with disabilities.

Creating environments that cater to the diverse abilities, needs, and learning styles of students can significantly benefit the growth of our special needs learners. An inclusive approach to design provides equal access to education and creates a sense of belonging, empowerment, and respect among a community of learners.

For students with severe disabilities, inclusion means balancing their needs and providing individualized accommodation, care, and instruction. The development of Individualized Education Plans (IEP) has become a key component of special education. These plans outline the specific accommodations and support each student needs to succeed in general education settings while also addressing unique disabilities and needs. IEPs are completed for every student who needs additional learning assistance.

There are specific instructional and care strategies that educators use to ensure the best outcomes for students with disabilities and to balance the goal of inclusion with the need for individualized instruction. Collaborative Planning between special education instructors and general educators is essential. Master Scheduling and Clustering are techniques used to build daily schedules and group students based on students’ IEPs, considering specific logistical factors of the school day.

Kennedy High School Modernization—Expanding Equity and Access

HMC Architects is currently in the middle of a comprehensive modernization project at John F. Kennedy High School in the Granada Hills section of the San Fernando Valley, just north of Los Angeles. This multiphased $130 million project will update a significant part of the 2,400-student campus, including constructing a new two-story classroom building—a state-of-the-art learning environment designed within the context of the campus’ midcentury New Federalist style.

Kennedy High School is nationally known for its acclaimed magnet and CTE programs in technical disciplines and the arts. This renovation will provide much-needed next-generation facilities to support those pathways, including revamping a performing arts theater. One of the key drivers of this project is to bring the special education facilities campus-wide up to modern standards. Approximately 14 percent of the student body has some type of special need or disability. (Ten percent of the special education population is typical for a school. At Kennedy, special education students can attend up to 20 years of age, accounting for this higher percentage).

The current classroom configurations are the product of an earlier generational approach, and they need to catch up to current standards and requirements. For instance, without adjacent facilities, in some cases, students with more significant physical disabilities need to call a nurse every time they need to use the restroom— the stigma is obvious.

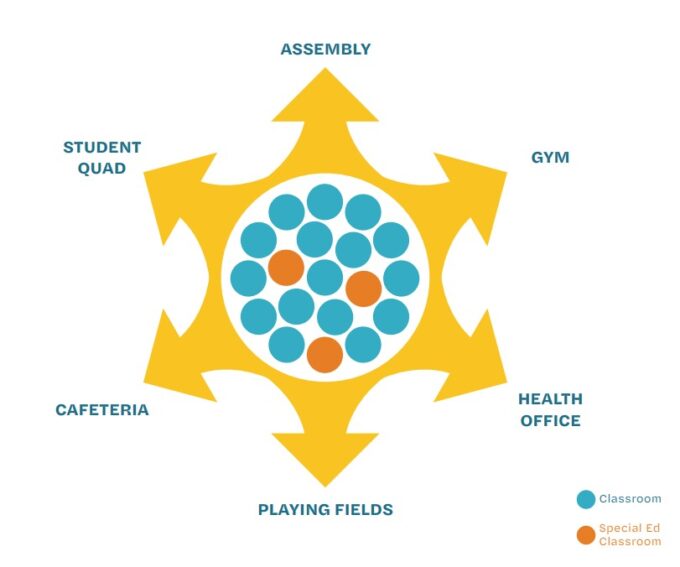

There are three types of special education classroom configurations across the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) each with progressively more square footage and additional support spaces that correspond to more significant disabilities. The strategy is to provide direct access to enhanced support spaces, including calming spaces, environments to learn different life skills, specialized apparatus, lifts, or other equipment. The planning process was especially challenging as we were designing for current needs and attempting to look at feeder elementary and middle schools to anticipate future special education needs.

Another key strategy has been integrating special education classrooms among general education classrooms to support inclusion. We removed portables that had previously housed special education classrooms to reach this goal. There had been a complete rework of floor plans in existing buildings. The design process has to address the student needs, operational needs, and regulatory requirements.

Supporting Student Wellness

Part of the Kennedy High School project includes relocating the health clinic strategically near the front of campus to serve students. There are separate entrances for each group for security and to provide privacy for both groups. Throughout campus, other wellness spaces have been included in the design.

We have created outdoor spaces where students can cool off when things become overwhelming. Sometimes, a person needs time to gather their thoughts. We have emphasized nature, natural light, plants, and greenery in these spaces. Research clearly shows the benefits of fresh air and open space for mental health. It sounds overly simplistic, but we are trying to create cheerful and not institutional environments.

LAUSD District-Wide Commitment to Equity

The modernization at Kennedy is part of LAUSD’s commitment to ensure every student across the district’s 1,300 schools has full opportunities to be included in educational and social experiences. The district’s position paper, Equity and Access for Students with Disabilities, outlines this focus, stating that the district’s goal is to bring “more students into inclusive settings commensurate with national standards” and that they are now “pushing for a systemic shift in mindset to be better aligned with those laws.” The paper says that through these efforts, the district “expects to see academic gains for all students, a positive impact on school culture, and a greater acceptance of diversity as a strength.” As the second largest school district in the nation, LAUSD has the unique size and reach to impact this issue broadly.

A High School Experience Like Everyone Else’s

In Los Angeles and across the country, significant progress has been made in removing barriers and developing better, more inclusive ways to care for and educate our most vulnerable students. There are a lot of people and organizations working hard on these problems.

If you spend time around students with disabilities, you start to see these questions in more human terms. Kids with disabilities and mental health challenges want a positive school experience, a campus experience like their peers—making friends and being part of activities—all the little things that make school years a formative time in a young person’s life. The idea of just trying to be a normal kid is a good thing for all of us to remember.

Benefits of inclusive practices for students with disabilities

- Higher rate of academic performance

- More satisfying and diverse friendships

- Higher student engagement

- Improved communication

- Less disruptive behaviors

- Peer role models for academic, social, and behavior skills

- Greater access to the general education curriculum

- Increased inclusion in postsecondary life

- More successful postsecondary outcomes

Benefits of inclusive practices for students without disabilities include:

- Greater gains in math and reading

- It reduces the fear of differences and increases social cognition

- Students gain better ethical principles and improved self concept

Author’s Note: Mental health and disability are highly complex issues. Due to the format limitations of this publication, this article is merely a high-level summary focusing on educational design and planning. There are many related clinical and behavioral topics that we have not explored here. For this reason, we include this list of further readings:

Design for How People Learn, Second Edition by Julie Dirksen, December 2015

Interior Design for Autism from Childhood to Adolescence by A. J. Paron-Wildes, October 2013