Louis Sullivan is famous for his axiom of “form follows function,” and his mentee Frank Lloyd Wright retooled it so that he believed that “form and function are one.” Wherever you stand in those philosophies, we should not deny the importance of taking into consideration the environment, form, function, and people’s interconnectedness as they apply to smart building design architecture.

Design in response to this self-evident truth is a reminder that buildings serve people, and both serve the environment. This is a constant reminder that architects are tasked with a role beyond simply the artifact’s visual delight, and therefore must respond in a vocabulary that speaks to environmental regeneration, human health, and wellness.

Green Building Design’s Natural Ties to Smart Buildings

The new generations of smart buildings aren’t just using technology to be more efficient, but they’re also being designed with nature as their model. Whole system integration, where the sum of the parts is collectively in a life-long partnership with the environment, has become the standard to strive towards when it comes to integrating the two. Today, a new social contact with nature is uncontested, absolute, and the bedrock to innovation.

One example from nature is how some organisms leverage fluids to maintain thermal stability, using the radiant transfer to exchange the majority of its energy. Designers can incorporate this approach by modernizing parts and assemblies to use thermally activated surfaces, which offer proximity thermal comfort that aligns with human physiology. Thermally activated surfaces are central to advancing whole building solutions, by introducing radiant fields to heat and cool and natural convection to induce ventilation, we can collectively achieve thermal comfort without the use of current forced-air based HVAC systems.

Challenges with Green Buildings

Challenges with Green Buildings

A green building’s greatest challenge is overcoming centuries of antiquated building parts that continue to dominate and limit the potential for smarter buildings to emerge. The post and lintel construction originated in the ancient world, has remained relatively unchallenged in today’s common framing conventions, which can vastly hinder and repress innovation.

While these approaches may have satisfied the fundamental needs of shelter and thermal comfort, carrying these techniques forward into the future have a serious impact on our finite resources. In order to make impactful progress, we need to focus on environmental partnerships that put an emphasis on decarbonization. For every green building that only accommodates the parts of the past, they further themselves from the full potential of becoming a smart building of the future.

Architects should consider how biology classifies organisms as a function of their physiological relationship to the environment. What if the built environment had a similar physiological classification that identifies this relationship, such as asking, ‘is your building an endotherm or ectotherm?’ One generates heat internally and is decoupled from the environment, and the other responds to the environment. Contemporary buildings are more like internal engines that are void of partnership with the environment, so reconfiguring this relationship is central to developing new parts, assemblies, and coherent whole systems that are designed to be climate-centric.

Looking to Nature for the Solutions

Looking towards nature as a model for architecture gives designers a vast library, packed with solutions. Phillip Steadman conveyed the concept elegantly in The Evolution of Designs. Steadman suggests that nature as a model should not be misinterpreted as a frail allegiance to the natural world or loose metaphorical comparisons of phenomena of nature, but instead that finding strength of analogies in nature are central to the genesis of design evolution, continued extension, development, and intelligibility of smart buildings. Another exciting approach to design is biomimicry. As proposed by Janine Benyus, biomimicry places ecology as the standard to judge the rightness of our innovation to solve human problems inspired by our social contract with nature.

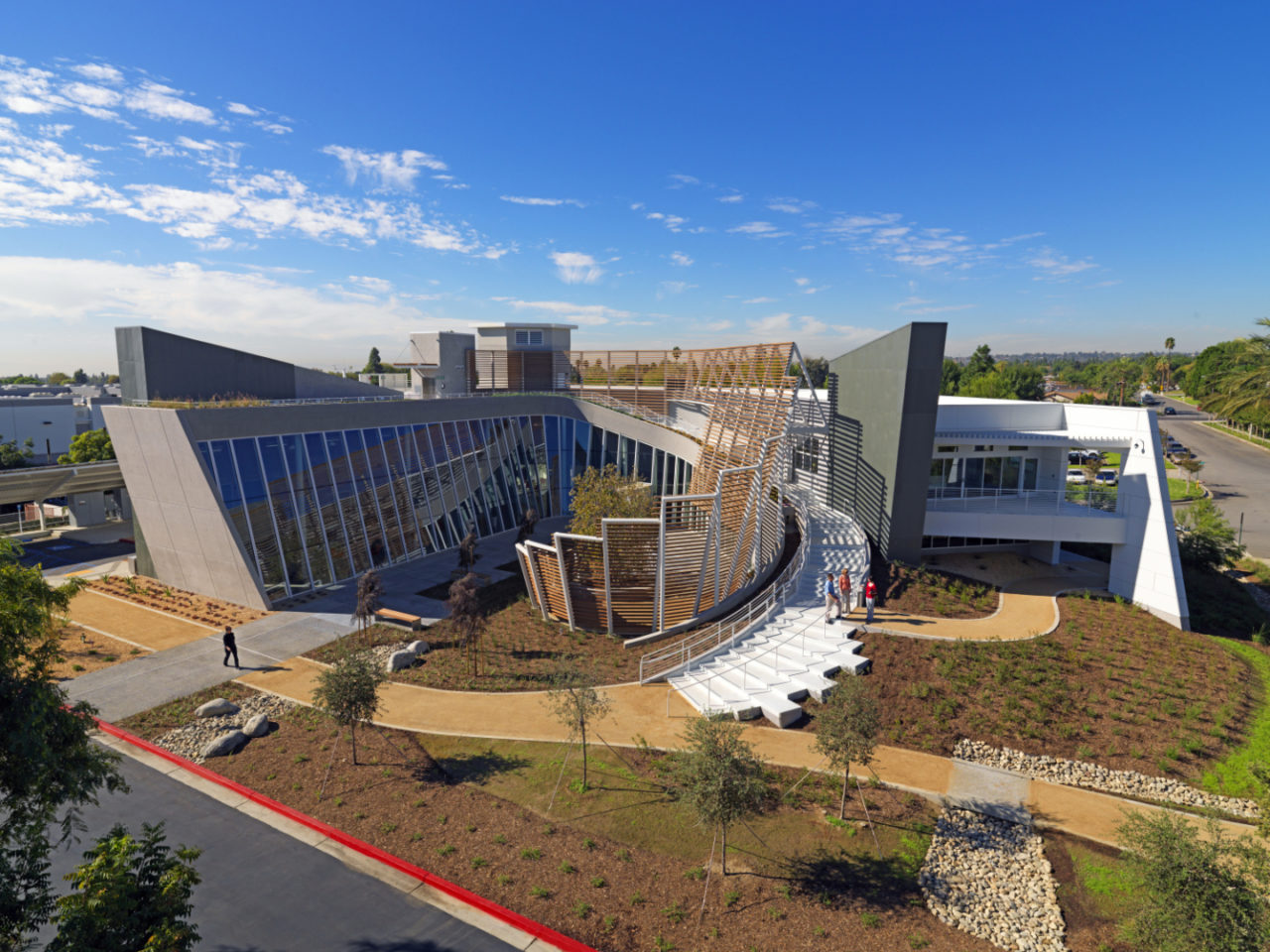

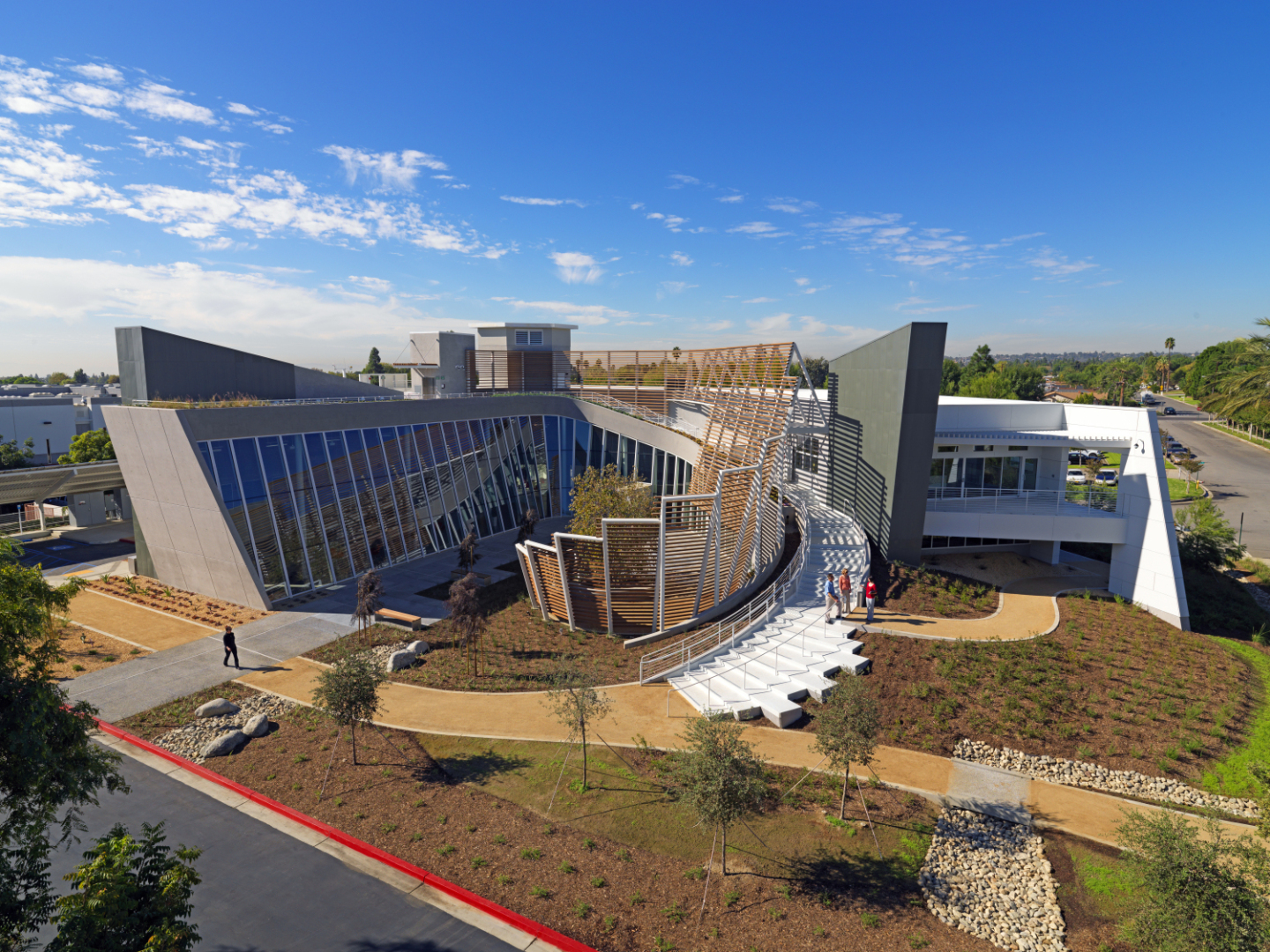

At the Frontier Project in Rancho Cucamonga, California, we set the curve for early adopters of smart buildings. The project’s combination of passive and active strategies set the tone of decarbonization and building electrification aspirations long before the 2030 Challenge. High thermal mass was used to dampen the region’s high summer temperatures, green roofs were incorporated to reduce solar gains, an evaporative cooling tower was designed to cool the building with no fan power, and carefully choreographed building geometry responded to solar angles to optimize daylight. Workplace health and wellness was important, so we made sure to provide plenty of views and access to nature. The baguette sun shades were upcycled wood from wine vats, while a large cistern harvests rainwater to a localized reuse aquifer.

The Frontier Project was an early integrator of smart building concepts and host to IoT of today with scientific equipment and an array of sensors to measure, store, and report building performance. The project was a placed-based solution with extensive integration of bio-climatic sensitivity that invited the environment to inform the design process and become a life-long learning partner for our firm as well as for the community.

There is no one recipe for smart building design architecture nor should there be one. Instead, there should be agents of change that challenge antiquated building blocks and receptive to innovation or innovate themselves. We propose that façades are prime to go beyond a single purpose and serve multiple purposes leading to smart buildings and opportunities to environmental collaboration and social justice.

There is no one recipe for smart building design architecture nor should there be one. Instead, there should be agents of change that challenge antiquated building blocks and receptive to innovation or innovate themselves. We propose that façades are prime to go beyond a single purpose and serve multiple purposes leading to smart buildings and opportunities to environmental collaboration and social justice.